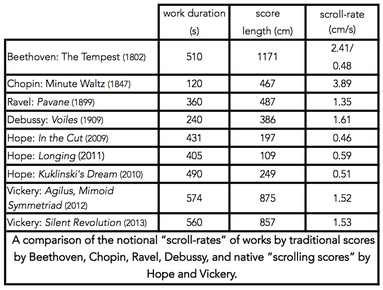

What is a “normal” (or at least average) reading rate for a score and how does the rate impact upon the amount of sonic detail that is capable of being represented? The table below compares the notional average rate at which the score progresses as the performer reads the work: its “scroll-rate”. The scroll-rate is calculated by dividing the length of the score by its average duration.

The works are varied: Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor Op. 31 No. 2 (1802) (The Tempest) first movement includes significant changes of tempo in which the performer would be reading at different rates; the Chopin Waltz in D-flat major Op. 64 No. 1 (1847) (Minute Waltz), Ravel Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899), Debussy Voiles (1909) might be considered examples at the high, low and centre of the scroll-rate speeds. These rates give an indication of what is an acceptable and perhaps even conventional speed to read musical notation.

The final five works on the table are “scrolling scores” by Cat Hope and Lindsay Vickery, in which the score moves past the performer at a constant rate on an iPad screen. There is, at the least, a psychological distinction between this paradigm, where the performer is forced to view only a portion of the score at any time, and the fixed score where the performer directs their own gaze.

The scrolling score, although highly useful for synchronising musical events in non-metrical music has particular natural constraints based on the limitations of human visual processing: at scroll rates greater than 3 cm/s the reader struggles to capture information; information dense musical notation may significantly lower this threshold; reading representations of fine metrical structures in a scrolling medium is problematic. The problem may be caused by a conflict between the continuous movement of the score and the relatively slow (in comparison to the ear) fixation rate of the eye or simply a by-product of unfamiliarity with the medium, however the cause is currently unexplained.

The works are varied: Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor Op. 31 No. 2 (1802) (The Tempest) first movement includes significant changes of tempo in which the performer would be reading at different rates; the Chopin Waltz in D-flat major Op. 64 No. 1 (1847) (Minute Waltz), Ravel Pavane pour une infante défunte (1899), Debussy Voiles (1909) might be considered examples at the high, low and centre of the scroll-rate speeds. These rates give an indication of what is an acceptable and perhaps even conventional speed to read musical notation.

The final five works on the table are “scrolling scores” by Cat Hope and Lindsay Vickery, in which the score moves past the performer at a constant rate on an iPad screen. There is, at the least, a psychological distinction between this paradigm, where the performer is forced to view only a portion of the score at any time, and the fixed score where the performer directs their own gaze.

The scrolling score, although highly useful for synchronising musical events in non-metrical music has particular natural constraints based on the limitations of human visual processing: at scroll rates greater than 3 cm/s the reader struggles to capture information; information dense musical notation may significantly lower this threshold; reading representations of fine metrical structures in a scrolling medium is problematic. The problem may be caused by a conflict between the continuous movement of the score and the relatively slow (in comparison to the ear) fixation rate of the eye or simply a by-product of unfamiliarity with the medium, however the cause is currently unexplained.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed