2008

107 Tectonic: Vaalbara 2008 chamber orchestra and electronics 17m

Tectonic can mean both ‘the study of the earth's structural features’ and ‘the art of construction’. The work reflects both aspects of the word’s meaning. The written musical materials, performed with an orchestra of strings, winds, piano and percussion are quite simple, but may also be transformed by electronic manipulation. The instrumental sections are performed independently - using separate conductors, allowing the blocks of musical material to slide, grate and collide with one another like tectonic plates.

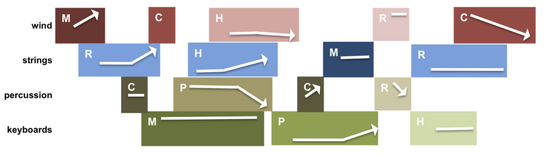

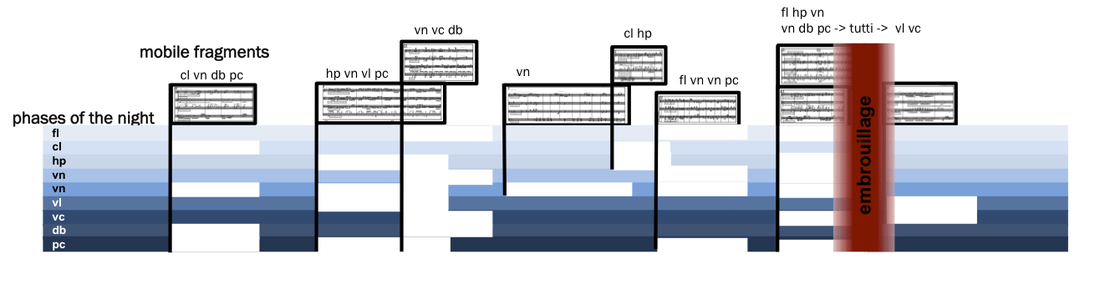

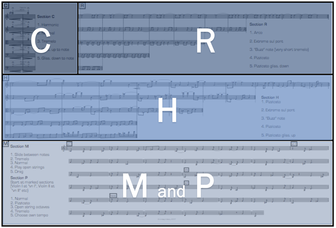

Tectonic employs a mobile score, in which five notated textures – C (chord), R (rhythm), H (harmony), M (melody) and P (polyphony) - are performed independently by four instrumental groups: wind, string, percussion and keyboard. The mobile score layout for the string players in Tectonic is shown in to the left.

Tectonic employs a mobile score, in which five notated textures – C (chord), R (rhythm), H (harmony), M (melody) and P (polyphony) - are performed independently by four instrumental groups: wind, string, percussion and keyboard. The mobile score layout for the string players in Tectonic is shown in to the left.

|

Coordination of this indeterminate structure is maintained by a computer that directs each instrumental group which of the notated textures to play and the tempo (between mm. 27 and mm. 135) at which to play it. The computer generated metronome pulses may accelerate, decelerate or remain constant throughout the performance of each texture.

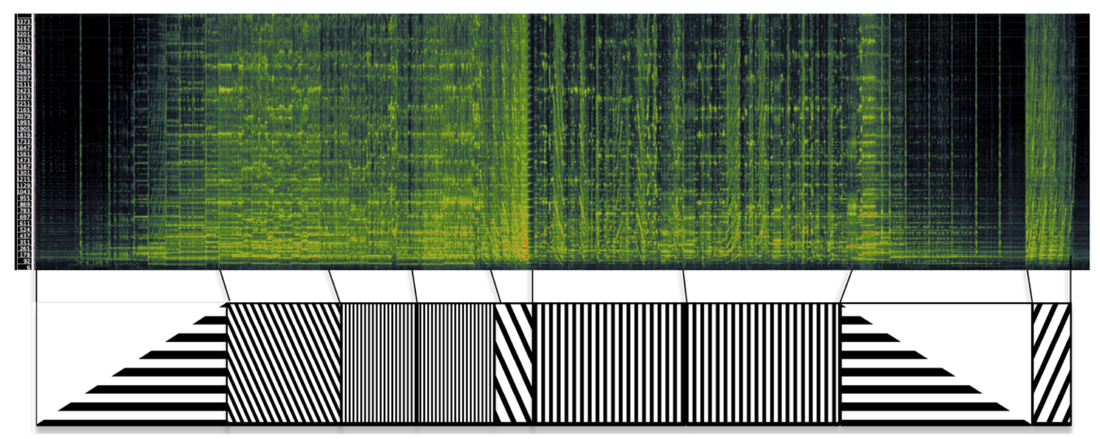

RIght is a representation of an example performance of Tectonic, showing the order of material performed and the changes in tempo taking place during the performance. |

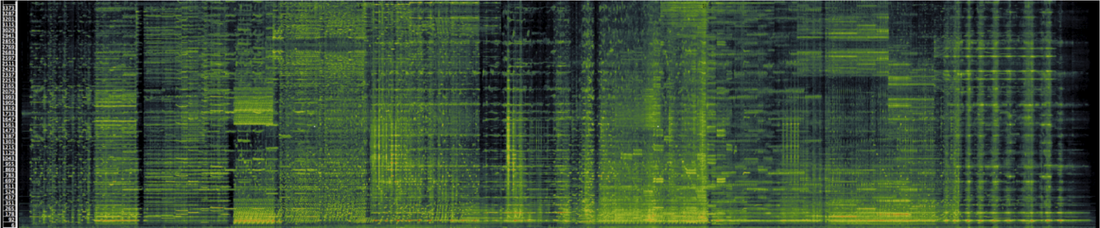

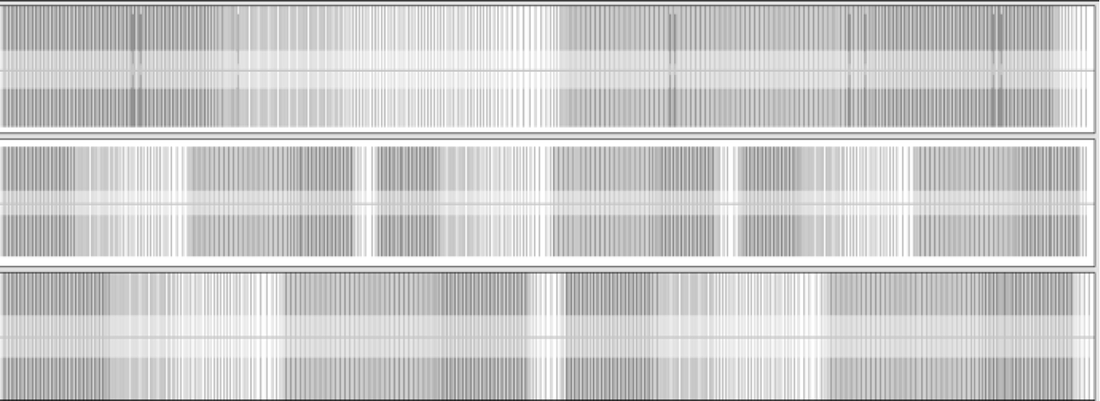

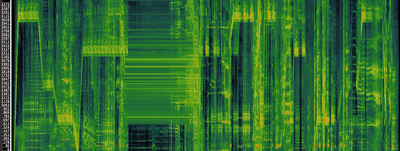

Below is a spectrogram of a performance of Tectonic, clearly indicating the presence of multiple and divergent blocks of texture. The important role played by audio processing is also evident in the contrasts in high frequency transformations of the live performers between sections. The polytemporal aspects of the structure are not visible at this level of magnification, but the presence of overlapping textural blocks in partially captured by the spectrogram.

2007

106 delicious ironies (series 3) 2005-10 instrument(s) and electronics 7m

Delicious Ironies was created as a vehicle to provide an extremely unpredictable and provocative sonic environment for the solo improviser. The intention was to use sound samples that were pertinent to the soloist, but also volatile and erratic enough to inspire an interesting improvised response in the moment. Series three explored the deconstruction of my own pieces Kreuz des Suedens, Cyphers of the Obscure Gods with the addition of a mobile score, improvisations by my group shmil, the works of others - Earle Brown’s December 1952 and improvisations by bassist Dr. Ian Woo.

|

delicious ironies (anakanak) 2010 delicious ironies (shmil) 2010 delicious ironies (dr woo) 2010 delicious ironies (december 1952 redux) 2007 delicious ironies (kds) 2005 delicious ironies (cyphers) 2005 |

105 Chanson Invisible 2007 ensemble 4m

104 Nusa Indah 2007 ensemble 4m

103 éraflage 2007 flute, harp, string quartet, double bass and percussion 9m

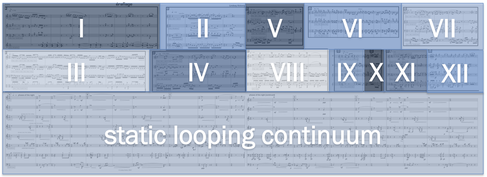

Sometime Surrealist artist Max Ernst explored a huge range of technical approaches to the creation of images in his vast body of work from 1909 to 1976. Amongst these techniques were Fumage (using black smoke on media), Frottage (rubbing over textured surfaces), Grattage (scraping the surface of works), Decalcomania (sticking images onto thick paint) and Asemic writing (invented glyphs and texts). Éraflage (scraping) is a homage to Ernst in the form of one of his most frequently used techniques: the Collage. This sonic collage of musical materials is spontaneously created with each performance. It consists of 12 musical fragments and one longer underlying scored texture, that are assembled into a work by through conductor or computer direction.

|

The musical materials can also be modified by a series of devices alluding to Ernst’s visual techniques: Éraflage (scraping distortion), Draguage (a sort of musical gravitational pull), Bruitage (transformation of materials into noise), Entropage (randomization) and Embrouillage (tangling). Ernst’s preoccupation with cosmological images, particularly in his later works, is reflected in the structure of the musical fragments that expand from a “singularity” of five pitches to a scale of 25 notes.In Éraflage two formal structures co-exist: one a continuous static-textured loop (called “phases of the night”) of 27 bars at a constant tempo, that is performed throughout the work; and the other a “mobile” collage of 12 musical fragments with five varied tempi.

The mobile paper score for the work comprises the “full score” (shown above), including the “static looping continuum”and the twelve fragments. In performance, the computer coordinates the path of each individual player. At indeterminate junctures the computer instructs between two and four players via headphones to disengage from the continuous texture, and to perform one of the fragments. |

|

The players are coordinated both in the tempo of their performance of the fragment and in their return to the continuous texture via clicktrack. This gives rise to a polystructure comprising a dynamic permutative collage and a static looping continuum. A schematic representation of this structure is shown below.

2006

102 warnasunda 2006 wind band 9m

2005

101 zwitschern 2005 clarinet, violin and theorbo and independently controlled click-tracks 7m

99 particle + wave 2004 saxophone, 2 sundanese gamelan instruments and independently controlled click-tracks 7m

98 Whorl 2004 saxophone, celeste, percussion (or three instruments) and independently controlled click-tracks 7m

Tempo is one of the least explored musical parameters in live performance. In non-solo performance each additional player decreases the ability to change tempo by many times. Accurate continuous changes in tempo (ie accelerando and rallentando) are generally regarded as non-specific commands (ie we are not taught to rall. over a particular, exact duration). These understandings are embedded in our musical perception to a high degree. Even in electronic music, where tempo variations can be precise, they often cause a perception in the listener of separate streams of sound rather than elements of a composite texture. This mirrors the way in which timbres are unpicked perceptually by the listener and attributed to different sources.

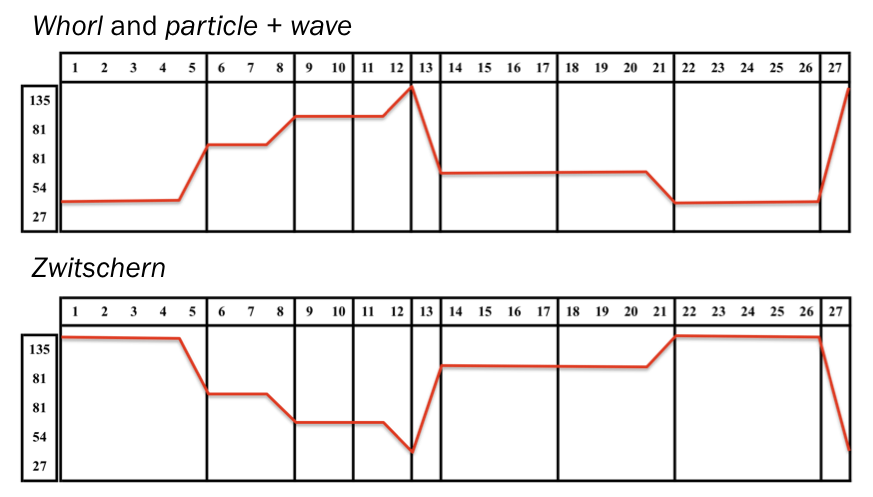

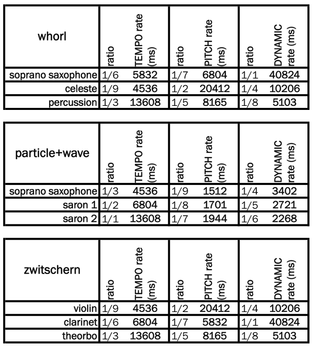

These three works were “studies” designed to develop and explore a methodology to control multiple tempi for live performers. These issues included: the factors determining whether simultaneous tempi are discerned as a fused texture or as separate lines; whether particular melodic or textural features draw attention to a particular line/tempo giving it primacy over other lines; and how the sense of pulse impacted by simultaneous continuous changes in tempo. Multiple proportionally related tempi determine different parameters in these three works. Nine tempi are assigned to three parameters of each of the three instruments. The figure to the left shows the relationships between these tempi , the absolute length of a beat in milliseconds and the parameter that is linked to each tempo.

These three works were “studies” designed to develop and explore a methodology to control multiple tempi for live performers. These issues included: the factors determining whether simultaneous tempi are discerned as a fused texture or as separate lines; whether particular melodic or textural features draw attention to a particular line/tempo giving it primacy over other lines; and how the sense of pulse impacted by simultaneous continuous changes in tempo. Multiple proportionally related tempi determine different parameters in these three works. Nine tempi are assigned to three parameters of each of the three instruments. The figure to the left shows the relationships between these tempi , the absolute length of a beat in milliseconds and the parameter that is linked to each tempo.

|

In each of the works, the players receive a clicktrack (with five tempi and connecting accelerandi and rallentandi), independent of the other players, as well as instructions on what dynamic, musical material and pitch set to play. Variations in tempo, pitch set and dynamics cycle through a pattern of fixed and continuous changes as illustrated to the right.The changing beat patterns of the three players in Whorl, particle+wave and Zwitschern are illustrated below.This arrangement creates an unusual set of conditions for the performers in which their listening skills are divided between synchronization with the computer generated clicktrack and ‘ensemble’ playing through listening to the other players. In rehearsal this initially results in a split focus – players tend to concentrate more on one task than the other. (Arguably this split focus also occurs to a degree when music with a unified tempo is first rehearsed.)

|

|

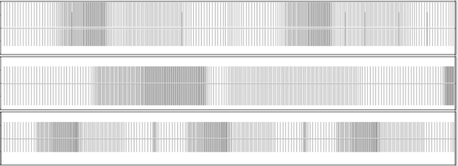

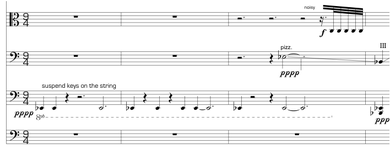

The conclusion drawn to the questions of textural fusion in polytemporal works was that the individual lines must be extremely simple in order to be differentiated. As a result, the scores for the three works are progressively less complex as shown to the left. Whorl employs five sections with different textures articulated through five varied pitch sets, the sections in particle+wave are only differentiated by the number of pitches and rhythmic variation, and in Zwitschern the sections are only differentiated by pitch.

|

100 shifting planes 2005 clarinet, harp, theorbo and string quartet 14m

Shifting Planes exhibits perhaps the most unambiguous example of the “cypher” process. The work explores the disjunction between the horizontal and vertical aspects of musical organization. It begins with horizontal planes of pitched-rhythms that coalesce into a rhythmic matrix of harmonies. The planes then break from the horizontal, cutting through the matrix diagonally to create arpeggios, and finally lining up vertically to create chords. This process allows the same materials to be exploited both rhythmically and melodically. The tension created through the search for a middleground between the horizontal and vertical planes results in glissandi that form an increasingly important part in the musical texture.

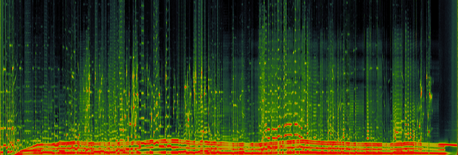

Below is a schematic representation of the formal structure of Shifting Planes in conjunction with a spectrogram of a performance of the work. The spectrogram confirms the presence of parametrical disjunction marking the block-form sections of the work. The schematic precisely illustrates the proportions of the “cypher” structure; slight divergences from the tempi indicated in the score, give rise to minor distortions to the temporal proportions of the work.

Below is a schematic representation of the formal structure of Shifting Planes in conjunction with a spectrogram of a performance of the work. The spectrogram confirms the presence of parametrical disjunction marking the block-form sections of the work. The schematic precisely illustrates the proportions of the “cypher” structure; slight divergences from the tempi indicated in the score, give rise to minor distortions to the temporal proportions of the work.